The Japanese obi, the belt that we spontaneously associate with the kimono, has never been a simple decorative ribbon.

Its width, rigidity, and the way it is tied have evolved over the centuries, and with them, the fate of inrō, those small precious boxes suspended from the belt with a netsuke.

Understanding this evolution allows us to better read the history of an inrō and place it in its context.

From discreet cord to Japan's iconic belt

In the early days of the kimono, the obi was just a relatively narrow cord used to keep the garment closed. Over the course of the Edo period, it grew in width, thickness, and visual importance, especially for women:

- The obi then becomes a major style element, with spectacular knots.

- fabrics are becoming more complex: brocades, damasks, woven or dyed patterns

- The belt structures the silhouette, emphasizes the waist, and creates a contrast with the kimono.

For men, the change is more moderate:

- The men's obi remains more understated, narrower, and functional.

- He must be able to hold the sword and carry the sagemono (inrō, pipe cases, purses, etc.).

The entire inrō + cord + netsuke ecosystem revolves around this men's belt.

Inrō and obi: a system designed for the belt, not the other way around

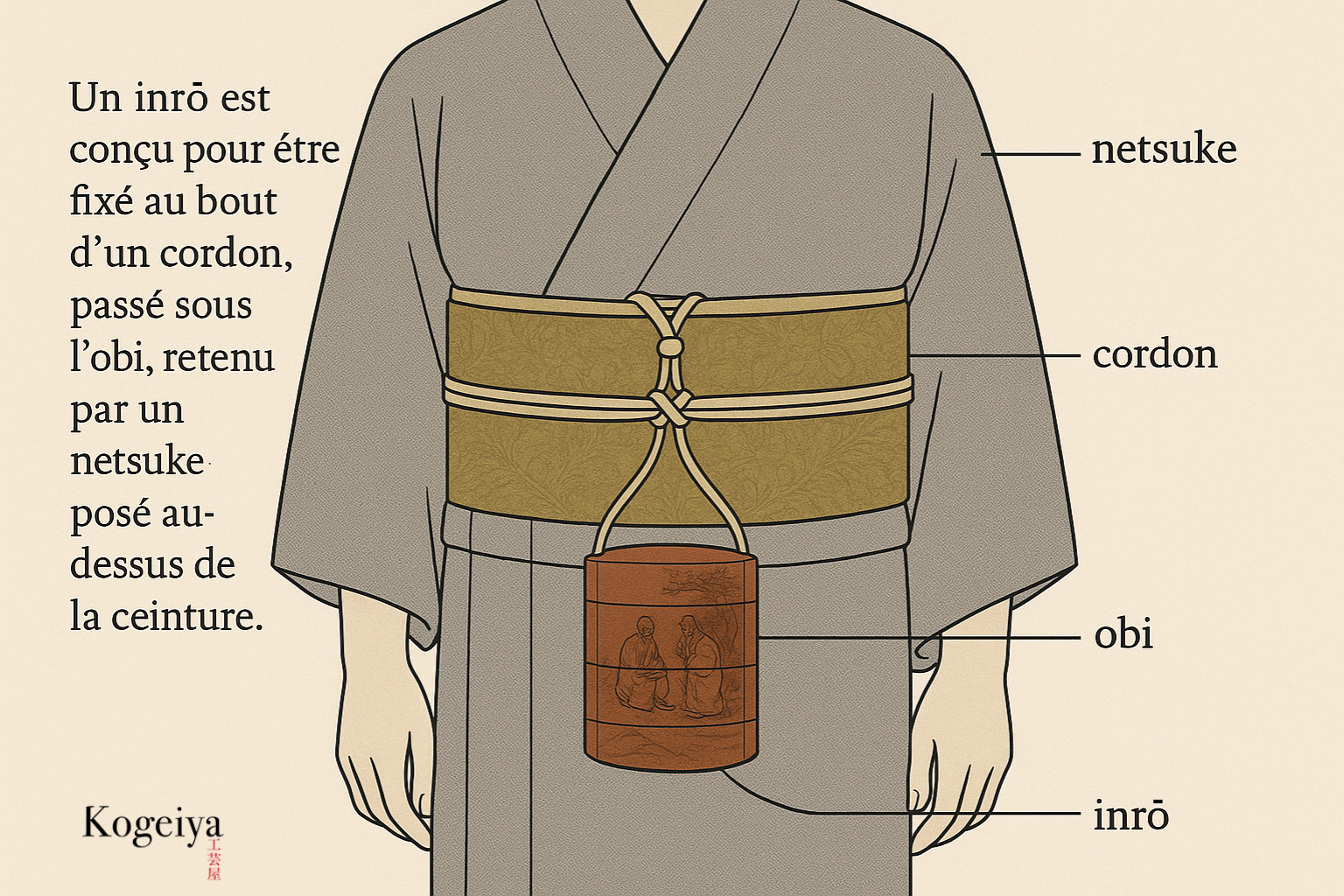

An inrō is designed to be attached to the end of a cord, passed under the obi, and held in place by a netsuke placed above the belt.

The variations in obi width between the end of the Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji era did not change the principle:

- The inrō remains a vertical object, composed of several stacked compartments.

- its size is adapted to the body and visibility under the obi, with no more than 1 or 2 cm difference in width;

- What changed most was the decorative language (nature scenes, heroic motifs, highly sophisticated lacquerwork) and the clientele.

In other words, the obi is evolving, but the inrō remains an accessory that is perfectly compatible with these changes. The technical impact is minor; the cultural impact, however, will be considerable.

When fashion changes: Westernization and the end of the utilitarian inrō

The major break came at the end of the 19th century with the gradual adoption of Western-style clothing, especially among men, leading to the widespread use of pockets, which made the inrō unnecessary for everyday use.

The men's kimono and obi became ceremonial garments, no longer worn on a daily basis.

Without an obi worn on a daily basis, the inrō loses its practical function. It then slips into another status:

- Japanese lacquer art object, made for knowledgeable collectors;

- production intended for the domestic collectors' market, then increasingly forexport to Europe;

- items often in perfect condition, with little or no signs of wear under the obi.

How the evolution of the obi has changed the collector's perspective

For collectors ofJapanese art and sagemono, the history of the obi is a valuable tool for interpretation:

A heavily weathered inrō, with consistent wear on the edges and cord passage, often suggests actual use under the obi during the Edo period.

An inrō with spectacular decoration, showing almost no wear, may indicate a piece from the late Edo or Meiji period, designed more for a collector's eye than for the belt; which is not without interest, far from it.

The disappearance of the male obi from everyday life also explains why inrō gradually became luxury items in their own right, sometimes sold with their netsuke as a set of art rather than a clothing accessory.

Thus, the evolution of the obi did not so much change the shape of the inrō as it transformed its status: from an elegant tool, securely suspended from the belt, it became one of the most refined emblems of Japanese art, detached from its original function.

Understanding this transition allows us to better date, interpret, and appreciate each inrō, linking it not only to kimono, but to the entire history of Japanese clothing and society.